After visiting a client at CES in January, I headed over to take a look at the audio gear.

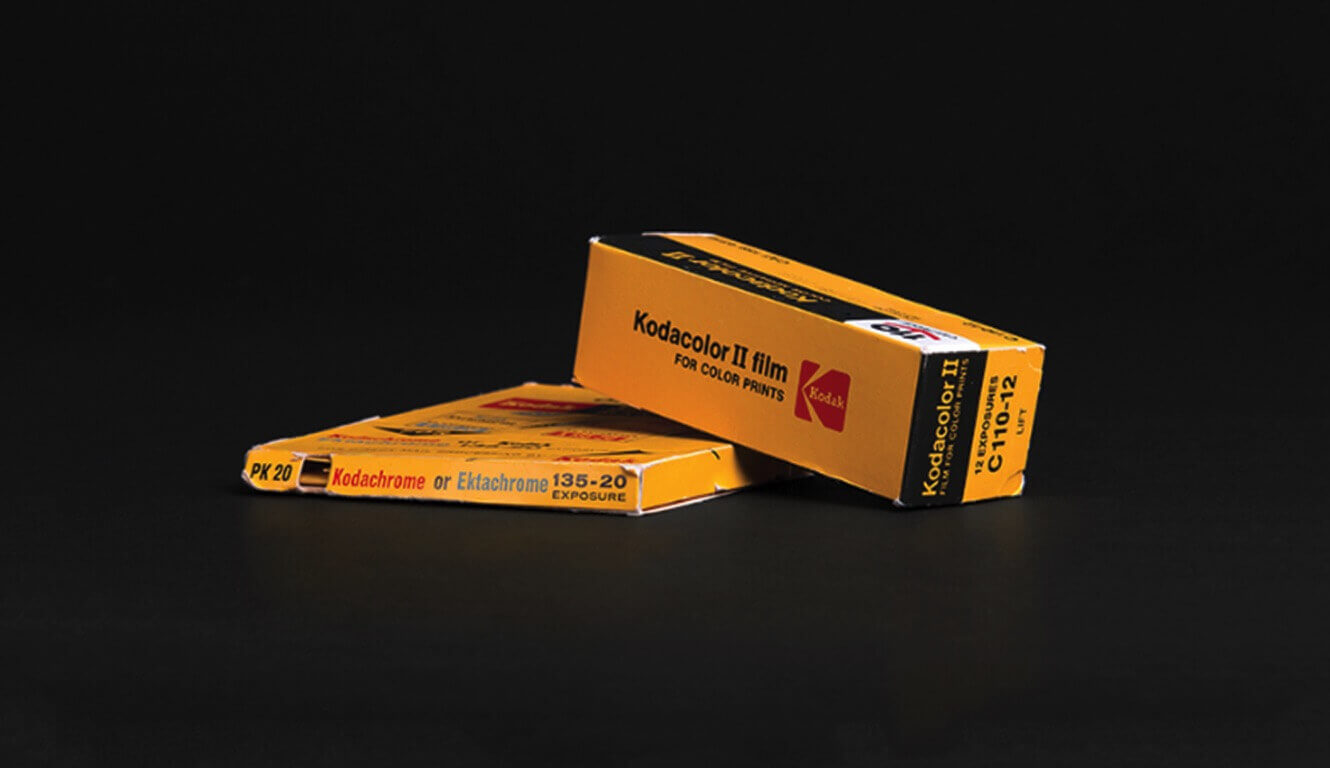

I’ve got an interest in that kind of thing, and with another client in the category, I wanted to know what the competition was up to. I did see a lot of interesting stuff, but on the way out, a Kodak-yellow brochure caught my eye. It was, in fact, Kodak. Selling headphones. Now, I have a lot of respect for the Kodak brand and its historical context, but I picked up this brochure and among the handful of questions I asked myself—some of which I’ll get to later—was this one: What business does Kodak have selling audio equipment?

The headphone market is booming today with the clear category leader, Beats, securing its sound cred from company founders, Jimmy Iovine and Dr. Dre. And our client, Shure, has also been successful with headphones, due in large part to a long history of audio excellence. It’s no surprise, though, that any brand—qualified or not—would want a piece of the headphone market, given the seemingly endless demand.

But this story isn’t just about seizing a marketing opportunity. For Kodak, it’s part of a larger narrative. If you look online, it’s not hard to find any number of in-depth analyses of Kodak’s demise. In fact, a recent article in The New York Times took its own thorough and rather unforgiving look at Kodak’s “ruinous” missed opportunities. Part bleak speculation, part post-mortem, the article examines the possibility of Kodak rising from the ashes—and literal rubble—of Rochester. And only time will tell.

Now, for anyone who didn’t follow the spectacular fall from grace of the American giant, the CliffsNotes version reads like this:

The Kodak empire began in 1889 when George Eastman founded the company that would become a household name. Over a hundred years later, shares were trading above $94, and in 2012, Eastman Kodak became a penny stock. The company filed for bankruptcy and was delisted from the NYSE.

For our purposes, though, the story begins in 1975, when a Kodak engineer built the world’s first digital camera. The surrounding details vary, but common lore holds that the company scrapped the idea to avoid undermining their cash cow—film and printing. And in that moment, Kodak unwittingly orchestrated its own downfall, and, as The Times noted, they “became a cautionary tale about what happens when a tech company is slow to change.”

Admittedly, it can be difficult for a century-old company to stay relevant, particularly over the treacherous analog-to-digital straits. A little over 125 years ago, right around the time George Eastman was working on his first patent, Thomas Edison filed his for the phonograph. Eventually his tin cylinder gave way to wax, cylinders gave way to discs, and then for nearly a century, vinyl was king until the compact disc appeared in 1983.

When the spectre of digital media showed up, the record companies didn’t want to give up the lucrative CD format. They thought they had a product that could compete; this wasn’t cassette tapes, after all. So they rejected the opportunity to create their own industry-wide digital music portal. Nobody’s gonna buy songs individually. What about the concept album? Liner notes? It’ll never happen. And then iTunes changed everything, becoming both the industry standard and a $12-billion-a-year business. And even that didn’t last. Here we are a decade later, and digital music sales are down while streaming is up. To fight obsolescence, one must always be looking ahead.

While the record industry did not fare so well, others did. Legacy doesn’t always have to be a liability. Consider Shure. For going on ninety years, the audio company has successfully parlayed its strengths into staying power. Their microphones appeared nearly everywhere—on World War II battlefields, in front of JFK, on stage with Frank Sinatra, and, most famously, immortalized on the 29-cent Elvis stamp. So the crooners made all those records, vinyl had its long heyday and phonograph cartridges did too. There, Shure had cornered the market—nearly every needle that was set down on an album had the Shure name.

So back to the eighties. When the digital CD came along, it upended the vinyl record and by extension, the phonograph cartridge business. But Shure didn’t falter. Instead, it doubled down on microphones, and continued to evolve and innovate, finding the right opportunities at the right time, gradually gaining a leadership position in wireless mic technology.

But timely evolution through innovation isn’t the only story here. And yes, this story is about Kodak. And more than that, it’s about brand authenticity. The move from analog to digital is littered with brands that thought they knew their audiences. As Simon Sinek famously stated in his TED talk, “People don’t buy what you do; they buy why you do it. And what you do simply proves what you believe.” As so many have noted, Kodak didn’t understand that its customers were investing in their own memories, not in paper. As business evolved, Kodak didn’t.

And though the deep commitment to film that Kodak had was admirable, it was fatally misguided. And that tragedy brings us back to another: the brochure that started this whole thing.

Clearly, someone licensed the name to sell these headphones. It says so, right at the bottom: “The Kodak trademark and trade dress are used under license from Eastman Kodak Company.” In fact, Google that sentence if you want to see what Kodak has been up to. It’s an indiscriminate fire sale, the licensing of the Kodak name.

If your brand gets vulnerable for any number of reasons—slow reactions, or a failure to diversify, or you’ve suffered from a litany of missteps as Kodak did—there are two ways of going. One is to build back up, relying on the brand’s strengths. What would that look like? How could Kodak have remained viable? Maybe partnered with a mobile phone company and manufactured a lens, or developed software and a photo app, capitalizing on the appeal of Instagram. Remind those whippersnappers who was responsible for the look that all those old-school filters are trying to emulate.

Or you can rely on the brand to bankroll your dying offering by auctioning off the dregs of your brand equity. Would you buy headphones from Kodak? Would you buy these headphones from anyone? Kodak has no business being in this space. There is nothing authentic about it.

Authenticity isn’t just a buzzword. It’s what people have always wanted, even if they didn’t know what it was called. To endure, you’ve got to stay in your expertise, and be an expert at knowing your audience. If you have to stray from your primary strengths, do so with caution. Study the hell out of whatever you’re doing.

And why does all of this matter anyway? It might be simple enough to say what everyone has already said: it’s woeful that a beloved brand is torn asunder. But getting back to the relationship between brands and the people who engage with them and sometimes even love them, it’s shameful because it’s personal. With Kodak, it’s a kick in the gut. It impinges on our memories. The logo and the Kodak moments are woven into our lives; the history of the brand is inexorably tied to our own. And here is this brochure with the headphones shoddily Photoshopped on the model’s head. It’s not just inauthentic; it’s salt in the wounds. It’s appalling, really.

Licensing out your name can be tricky. It’s pretty easy to dilute your brand in a hurry to where it’s devalued even as a licensing vehicle. In a lot of cases, unless you proceed with caution, it just doesn’t pay off. Not for a photography brand. Not for Kodak. If you are the world’s most famous visual imaging company, and you’re licensing your good name, you might hope your licensee would use beautiful photos of people wearing those headphones. But instead, digital photography has bitten Kodak again.

Is it a small thing—one brochure? Everything helps or hurts the brand. Everything your brand does perpetuates the vision. If it has your name on it, it should dignify your standards.

And now, Kodak is back on the NYSE, though one wonders if it can regain its credibility. Not everyone will suffer a fall like this. But you can be nimble in the face of change. It’s easier said than done, of course, and not everybody can do it—some have, some haven’t. But if you are faced with a paradigm shift, do your best. Be authentic and forward focused. Honor your brand. And failing that, hire a good Photoshop guy.